Out in the Woods

- December 20th 2024

- Out in the Woods

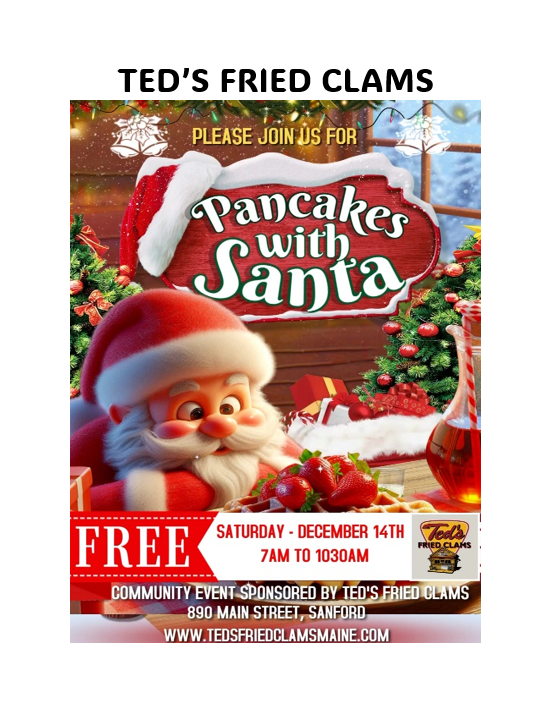

White birch bark shows dark, horizontal lenticels.

Photo: Kevin McKeon

Birch Trees’ Dark Lines Explained

By Kevin McKeon, Maine Master Naturalist

The first thing a white birch tree says to us is, “Look at the wonderful dark lines on my bark!” What’s up with these lines? In fact, they have to do with respiration, not decoration.

We’re all somewhat familiar with the photosynthetic process plants use to make their food. During photosynthesis, red and blue light wavelengths from the sun are absorbed by the chlorophyl pigment found in the chloroplasts of the plants’ cells. The green wavelengths are absorbed and are reflected to our eyes, making the plants’ leaves — which contain most of the plants’ chlorophyl — appear green. Plants use the absorbed light to synthesize food by processing carbon dioxide and water into sugar.

Eating this sugar involves respiration — the process of breaking down food molecules, like glucose, for energy — and respiration requires oxygen. Since plants and humans respire, they evolved a method to acquire oxygen: We grew lungs, and plants grew lenticels. One type of lenticel is that dark line on our birch tree. But they’re not always dark and they’re not always lines; they appear in various shapes, and they are found on plants everywhere. Those little dots on some apples are lenticels, too.

Lenticels are raised circular, oval, or elongated areas on skin, bark, and roots composed of loosely connected cells that form a spongy, rough, cork-like structure. This allows direct exchange of gases between plant tissue and the outside atmosphere and evolved from ancient plants’ small, pore-like growths called stomata. As plants grew larger, their stem and trunk support got thicker, so lenticels evolved to do the stomata’s job in these thicker skins. Stomata are still found in leaves and young stems. Birch’s lenticels emerge from under the stomata as the tree grows. As stems and roots mature, lenticel development continues in the bark — sometimes along the edges of cracks or fissures.

(An earlier Out In The Woods piece talked about burls. It is thought that entry of fungal infections that cause burls may sometimes be done via lenticels.)

Many fruits and vegetables, including apples, pears, and cucumbers, have lenticels. Sometimes lenticel development can indicate when to pick the fruit. Light-colored lenticels on some immature fruit darken and become brown and shallow as lenticels develop and grow, allowing more oxygen to enter the fruit, encouraging ripening. Often, this ripening process needs to slow, like when our produce is shipped from California and Mexico to our commercial food stores. The wax coatings we see on some of these foods hinder lenticular gas exchanges, thus increasing shelf life. The coatings also are added for consumer appeal, as we fussy consumers have grown accustomed to shiny stuff! Sometimes fruits are stored in oxygen-depleted/controlled rooms and storehouses to better control ripening and increase storage time and salable availability.

Back on our white birch tree: Lenticels also assist in light penetration through the birch’s thin bark where chlorophyl exists in the inner bark, thereby promoting respiration and photosynthesis, even in winter.

Burls: https://sanfordspringvalenews.com/out-in-the-woods-54/

Editor’s note: Did you see something unusual last time you were out in the woods? Were you puzzled or surprised by something you saw? Ask our “Out in the Woods” columnist Kevin McKeon. He’ll be happy to investigate and try to answer your questions. Email him directly at: kpm@metrocast.net