Out in the Woods

- May 10th 2024

- Out in the Woods

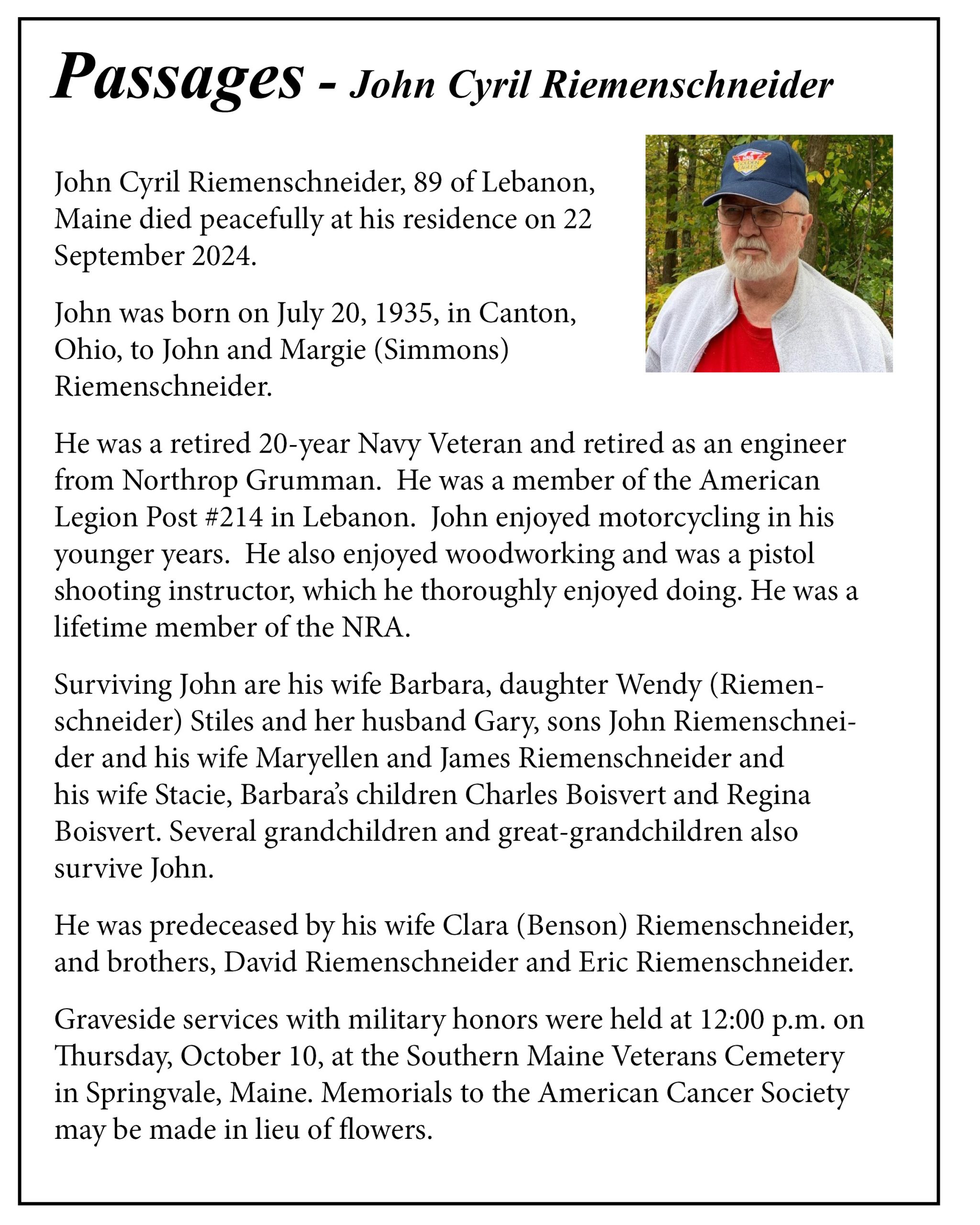

A painted turtle laying eggs in the sand along the Rail Trail

Photo: Kevin McKeon

Painted Turtles Have a Strong Homing Instinct

By Kevin McKeon, Maine Master Naturalist

The 15-million-year-old painted turtle can be found resting in and around the wetlands along many Sanford trails, basking on a log around Mousam River or maybe on a rock in Deering Pond. When hunting for shellfish along the muddy bottoms and munching on the various water plants in and along the riverbanks, it quickly juts its head into vegetation, agitating unsuspecting victims into the open water, where they are gobbled up. It also will skim the water’s surface with its mouth open to catch small particles of food. Algae, insects, crayfish, snails and fish are its favorites.

Being cold-blooded, and active only during the day, painted turtles gather body heat for the day’s activities by emerging from the morning water to bask for several hours, returning to the water to forage, basking again when chilled, and repeating until dark, when they drop back to the water’s bottom and sleep. Foraging turtles will cross lakes or travel up and down slow-moving rivers searching for water during dry times. Males travel 16 miles and females up to eight miles. They have homing instincts, mostly using visual recognition, and can find their way back home from over four miles away.

A female will lay four to 15 white, flexible eggs in her sandy/gravel nest, made in a sunny area two to four inches deep. She digs it using her tail and hind feet between late May and mid-July, usually close to water but sometimes up to 700 yards away. It’ll take her about four hours to complete, and she needs a temperature of about 80 degrees to do this, delaying the process if it’s too hot, too dry, or too cold. Only 50-70% of a local population’s females will lay eggs yearly, but those that do will usually lay twice. Sometimes, they’ll press their throat to the ground at various spots as if sensing moisture, heat, texture, or scent — or dig “false nests”— mysteries waiting to be solved! (More on turtle eggs in another article.)

In August and September, the young turtle breaks out of its egg using a special projection of its jaw called the egg tooth. In our area, the hatchlings may over-winter in the nest, emerging the following spring, eating their egg yolk material for early feeding. The temperature of the incubating egg determines the hatchling’s sex. At between 73 and 81 degrees, the baby will be male; others will be female. After crawling from their nests and instinctively finding the safety of water, hatchlings begin feeding and grow rapidly at first, sometimes doubling their size in the first year. Being easy to find and catch, the eggs and hatchlings are often eaten by rodents, foxes, coyotes, and snakes. However, the adult turtles’ hard shells protect them from most predators. Growth usually stops at maturity — about 7 years old for males, and about 13 for females — with the 10-inch females being a bit larger than males. The probability of a painted turtle surviving from the egg to its first birthday is only 19%. The annual survival rate rises to 45% for juveniles and 95% for adults, and they can live more than 55 years.

During the winter (October to March), the painted turtle hibernates, during which time its body temperature averages 43 degrees. It will bury itself on the bottom of a body of water, near water in the shore bank, in the burrow of a muskrat or in woods or pastures. Hibernating underwater, the turtle prefers a depth of less than seven feet and will dig down another three feet or so into the mud. The turtle now does not breathe but gets some oxygen through its skin. They are genetically adapted to survive extended periods of subfreezing temperatures with blood that can remain “supercooled” and skin that resists icing up. The hardest freezes nevertheless kill many over-wintering hatchlings. Their many unique adaptations — blood chemistry, brain, heart and particularly the shell — allow them to survive long periods with no oxygen and high lactic acid buildup and are the subject of many scientific papers.

Habitat loss is the primary threat to painted turtle survival. This includes filling in and drying of wetlands, removal of logs and rocks (needed for basking) from waterways and clearing of shoreline vegetation that allows increased predation and human foot traffic. Anthropogenic (human-related) activities and the relatively recent penetration of motorized use into nesting areas increase mortality on historic nesting sites along gravel paths, trails and roads. A significant survival threat is roadkill. Dead turtles, especially nest-seeking females, are commonly seen on summer roads. Roads also act as migration barriers causing genetic isolation, resulting in a lowering of the species’ evolutionary adaptation process. Some forward-thinking localities have tried to limit roadkill and isolation threats by constructing wildlife-friendly underpasses, highway safety channels and warning/crossing signs. Safely assisting turtles across the road is done by carrying them across the road.