Out In the Woods… A Keystone Species Benefits the Landscape in Many Ways

- August 25th 2023

- Out in the Woods

- beavers Sanford Trails wildlife

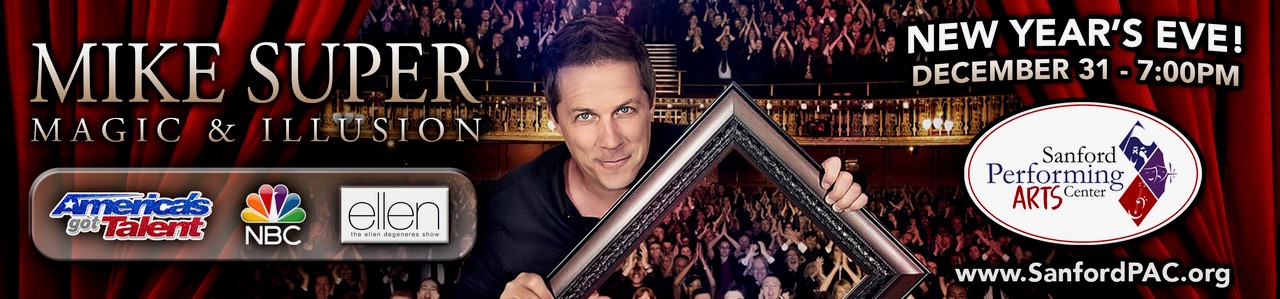

Canada geese and a beaver lodge are visible from the old Hobbs Mill at the foot of an impoundment of the Great Works River. The surrounding lands were conserved in a deal that allowed solar development at the airport.

Photo: Kevin McKeon

By Kevin McKeon, Maine Master Naturalist

To learn about beaver behavior, scientists once placed a domesticated beaver and some sticks in an isolated space, then from behind a wall, piped in the sounds of running water. The beaver started building a dam against the wall nearest the sound. Each time the sound was moved to another wall, the beaver moved its dam building activity. Thus, they demonstrated that even a beaver raised in captivity instinctively reacts to running water by trying to stop that sound.

These rodent engineers can be seen at various locations along the Rail Trail, Mousam Way Land Trust Reserves, and City-owned preserves. Beavers are considered a Keystone Species because their wetland-enhancing activities benefit many other creatures. Some managers of remote lands drop beaver by specialized parachutes to populate the landscape and restore other species.

Why repopulate areas with beaver?

Beaver wetlands are among the most biologically productive ecosystems in the world and aid humans by mitigating flood damage. A series of dams along a stream slows turbulent flows and encourages vegetation growth, which holds existing soil in place and reduces riverbank erosion. The impoundments spread water over a larger area, creating a wetter habitat, with the water seeping through the soils, recharging the water table, increasing resistance to droughts and fires, and offering a water supply to the landscape’s critters and to firefighters.

As beaver cut trees for their food, dams, and lodges, a mosaic of lush land and water vegetation is created, increasing the abundance and diversity of insects, which provides more food for fish, mammals, birds, amphibians and waterfowl, as well as the critters that eat them. More sunlight reaches exposed water, with a higher intensity, triggering an explosion of biological activity. Water quality is enhanced by the actions of microscopic creatures and algae as they absorb dissolved nutrients and eat organic wastes. The water becomes rich in nutrients. The organic material deposited by these activities supports the emergence of specialized microscopic organisms that can detoxify and neutralize human-created pollutants like heavy metals, pesticides, and fertilizers. This biologically active, submerged beaver meadow habitat could be termed “The Landscape’s Kidneys,” purifying water and allowing the capture and sequestering of substantial levels of carbon, as the wetland vegetation seasonally dies, sinks, and is covered with silt.

When the beaver’s food source dwindles, their dams are abandoned and erode, slowly releasing the impounded water, leaving behind a rich soil. When the food sources rebound, the beaver will return. This process repeats over the centuries, eventually creating the basis of many of today’s productive farmlands.

The beavers build channels to aid in their foraging, extending the wetland to provide greater habitat for many different species. The shallow channels, wetlands, swamps, and fens associated with beaver dams provide ideal breeding habitat for reptiles and amphibians, which are food for heron, bittern, rail, egret, and various raptors. The abundance and diversity of songbirds is enhanced. Flooded large trees slowly die and become home to creatures of all sorts. Insects burrow into the decaying wood, feeding all kinds of birds; woodpeckers then create nesting cavities, which are then excavated further for larger, cavity-dwelling creatures like owls, ducks, raccoons, foxes, and others. Beaver winter food caches often pierce the pond’s surface, provide nesting sites for loons and geese, and basking sites for turtles and snakes.