Out in the Woods

- January 27th 2024

- Out in the Woods

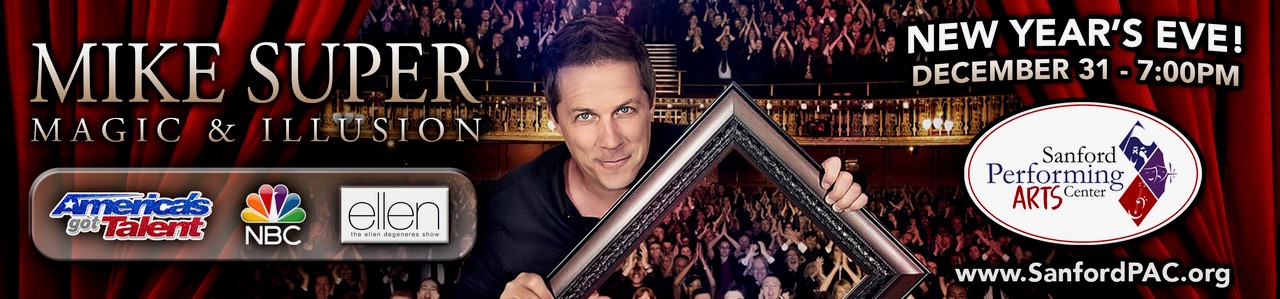

A snowshoe hare in winter coat stands out on bare ground

Photo: Public Domain

Editor’s note: Did you see something unusual last time you were out in the woods? Were you puzzled or surprised by something you saw? Ask our “Out in the Woods” columnist Kevin McKeon. He’ll be happy to investigate and try to answer your questions. Email him directly at: kpm@metrocast.net

Snowshoe Hares Experiencing Camouflage Mismatch

By Kevin McKeon, Director, Mousam Way Land Trust

The woods of Sanford are home to both rabbits and the snowshoe hare. Hares and rabbits are related, but there are some key differences. Hares tend to be larger than rabbits and have longer legs and bigger ears. When threatened, hares use their big feet to flee at the first sign of danger, but rabbits typically freeze and rely on camouflage. Hares are born fully furred and ready to run, but rabbits are born blind, hairless, and helpless, requiring considerable attention during their first two weeks of life. The most recognizable difference between the two species is that snowshoe hares turn white during the winter while rabbits remain brown.

The two rabbit species found in Maine are the Eastern cottontail and the New England cottontail. The snowshoe hare and Eastern cottontail are found everywhere. The New England cottontail is rarely found north of Portland, is listed as a state endangered species, and is a candidate for listing under the Federal Endangered Species Act. It is illegal to hunt or trap these critters. Loss of habitat has caused a steep decline in New England cottontail populations throughout their range in New England and New York. But this time, we’ll talk about the snowshoe hare.

Shy and secretive, these hares spend most of the day in shallow depressions, called forms, scraped out under clumps of ferns, brush thickets, and downed piles of timber. They make their home in thick bushes, especially in the re-growth of recently cut areas. Being most active at night (nocturnal), look for them at dawn and dusk when they can be seen browsing among the leaves of fresh, young sprouts of just about anything green. As winter nears, they’ll eat twigs, buds, evergreen needles and bark, following well-worn forest paths to feed and wandering up to five miles when food is scarce.

Their thick, brushy habitat shelters them from cold winter winds, and provides cover and escape paths against their many predators: owls, hawks, eagles, crows and ravens, fox, bobcats, coyote and, especially, the Canada Lynx. The snowshoe hares’ winter color-change adaptation can help protect them against predators. Their winter-white fur blends in with the snow and turns a reddish-brown in spring and summer, blending with the forest floor and scrub shrub areas. But global warming is causing snow to coat the forest floor later in the season and causes an earlier snowmelt, so the hares’ still-white coats now act as targets for their predators, reducing survival rates. Studies indicate that the hares do not realize that their fur has lost its camouflage adaptation, increasing their vulnerability to predation. A lot of critters love to eat hares: 75% to 90% of juveniles and about 60% to 80% adults die each year, so it’s a rare hare that lives to be a year old!

Fortunately, snowshoe hares are prolific breeders. Females have two or three litters each year, which include from one to eight young per litter. Young hares (leverets) require little care from their mothers and can survive on their own in a month or less. Their populations fluctuate cyclically about once a decade, and greatly impact the hares’ predators, particularly the bobcat and Canada lynx.