Out in the Woods

- November 19th 2023

- Out in the Woods

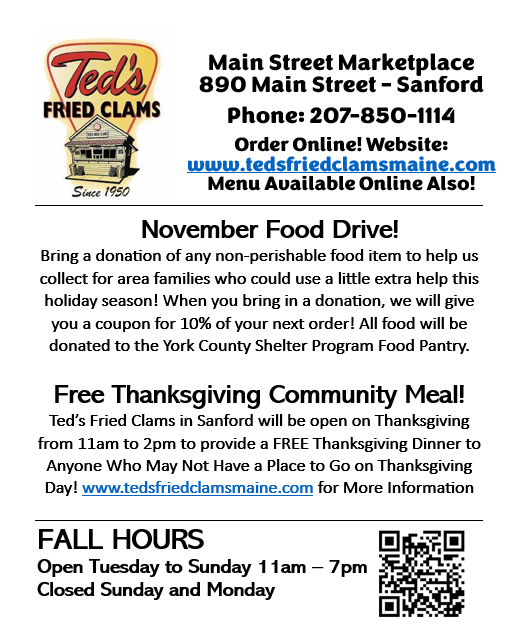

A turkey shows off bright colors

Photo: Kevin McKeon

Editor’s note: Send your nature-related questions to “Out in the Woods” columnist Kevin McKeon. He’ll be happy to investigate and try to answer them. Email him directly at: kpm@metrocast.net

The Origins of Turkeys

By Kevin McKeon, Maine Master Naturalist

Turkeys were first domesticated in Mexico about 3000 years ago by the pre-Aztecs—not for meat, but for feathers. The area of feathers below the feather tip is made up of very fine, downy plumage. After being softened by soaking, the feather’s tip was removed. The remaining wet feather was fastened to and wrapped around a cord made from the yucca plant, forming a sort of turkey feather yarn which was woven into blankets and robes. 12,000 to 15,000 feathers were required to make a small 4’ x 5’ infant’s blanket. Each feather was wound by hand! Feathered adornments were also used for rituals and ceremonies. Here’s a short video about the process.

Turkeys were again domesticated about 2300 years ago by a different people…the Native American Ancestral Pueblos, previously known as the Anasazi. They also first used them for their feathers, then began eating them about 900 years ago. When the Spanish arrived in the New World, they transported the turkey to Europe. It resembled a bird from Africa brought to England via Turkey. The name stuck so now we have the “turkey”. Several varieties were developed to meet demand. Then, in the 1700’s, these European breeds were brought back to the United States. So, both our domesticated and wild turkeys descend from the Aztec breed.

Our dinner table turkeys can weigh up to twice that of the 25-pound wild birds and are usually too heavy for flight. But their wild cousins can outrun a galloping horse for a short distance and can quite gracefully fly for over a mile at spurts of 55 miles per hour! When they need to, turkeys can swim by tucking-in their wings, spreading their tails, and kicking.

They are often seen scratching the ground for food: acorns, seeds, berries, small insects and even small amphibians. In the winter, they’ll gobble down Hemlock buds, ferns, and mosses. At night they’ll roost on tree branches. About 90% of all turkeys live in the U.S. The rest are in Mexico and Canada. Since the mid-1960’s, restoration efforts were so successful that hunting is allowed wherever they roam. They are second to deer as the most hunted game species.

The skin on a turkey’s throat and head is un-feathered and can change color from flat gray to striking shades of red, white, and blue when the bird becomes distressed or excited. Their “snood” (the flap of skin that hangs over the turkey’s beak) and their “wattle” (the flap of skin under their beak) will be bright red when the turkey is upset or during courtship.

In the spring, the hen will lay up to 18 eggs on a nest she makes on the ground, under a bush. A month later the “poults” hatch. For two weeks, unable to fly, the hen will care for them…roosting on the ground and teaching them to forage in fields for grasshoppers and other insects. When threatened, she’ll huddle with them with wings and tail spread, being very still. If they are detected, she gives a vocal command to her young to remain “frozen,” and feigns an attack on the intruder, simultaneously making a “putting” sound to quiet her chicks. By the time they are a week old, they’ll run away. A week later, they’re able to fly into thick shrubs and low branches. A week after that, they’ll fly into trees. A year later, the chicks leave mom for their own adventures.

Benjamin Franklin once wrote a letter to his daughter criticizing the original eagle design for the Great Seal of the United States, saying that it looked more like a turkey and that it’s “a bird of bad moral character” and that it “does not get his living honestly” because it steals food from the fishing hawk and is “too lazy to fish for himself.” He called the turkey “a much more respectable bird” and “a true original native of America…He is besides, though a little vain & silly, a Bird of Courage.” So, although he defended the honor of the turkey against the bald eagle, it is a myth that he proposed it as one of America’s most important symbols.